This post is the second part of a series. Each post uses a different metaphor to illustrate a specific aspect of the learning process. You can check the other posts The City of Learning and The Pyramid of Expertise.

Knowledge is lumpy and uneven, with small areas of expertise separated by deserts of ignorance.

— Kevin Kelly, “Out of Control: The New Biology of Machines, Social Systems, and the Economic World

Knowledge and Nature are very similar. Both are ephemeral, constantly changing, and always full of surprises. In this post, the trip continues outside of the city. We will explore the world around us from a new angle, still using learning as our means of transport.

The Biodiversity

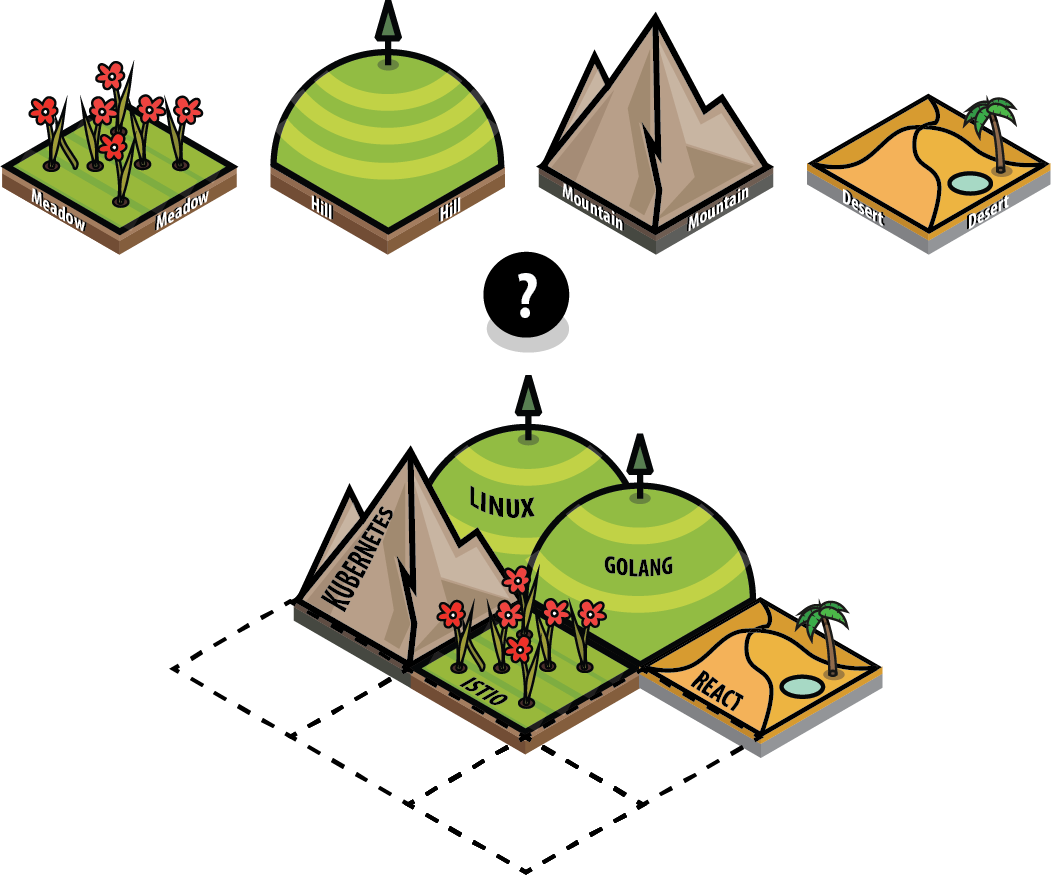

Welcome in a world of knowledge, your world of knowledge. If you observe around you, you will see a multitude of varied landscapes, reflecting your different levels of competence in a long list of topics. Each of us has a unique background, and thus unique knowledge. In the same way there are no two places on the earth that look exactly alike, there are no two landscapes of knowledge that are identical.

In this section, we will categorise the different types of landscape we may encounter during our journey.

The Garden of School

Learning starts as soon as we’re coming into this world. We learn a lot during infancy and this explains why babies have twice as many neurons as adults, in a brain that’s half the size. But the skills that make us a very knowledgeable species are learned later, when we are starting school.

At school, we learn essential skills like reading and writing. Without that knowledge, we would not go very far in life. We also discover a multitude of disciplines—mathematics, geography, history, literature. Of course, we only scratch the surface of all of those subjects. School plants the seeds that will be helpful for us to build new knowledge on it. Some will turn into magnificent plants. Others will not.

In the end, the goal of school is to teach us how to learn. “Education is the kindling of a flame, not the filling of a vessel” said Socrates. The reality is, however, very different, otherwise the MOOC “Learning How to Learn” would not be the most popular MOOC of all time.1

School is just the starting point, the entry door of a larger world.

The Hills of Higher Education

Universities, and other higher education programs, help students learn advanced skills. You stop learning what everybody else is learning. You expand your knowledge in new directions through specialization. You may choose for example among engineering disciplines like biology, computer science, aerospace, or among liberal arts like linguistics, history, sociology. What you learn will determine your profession, help you get a job, so that you can make a living from it.

Upon graduation, you have a solid background on a few complementary subjects. During the course of your Master of Computer Science, you will learn about Hardware Architecture, Software Engineering, Programming Languages Theory, Databases, Algorithms, Statistics, Machine Learning, and so much more. Each of these subjects forms a hill in your knowledge landscape. Depending on your grades, the hills will be higher or lower than the hills of your classmates. And depending on your career, some of the hills will turn into magnificent mountains, or others will completely disappear after a landslide caused by erosion.

The Meadow of Superficial Knowledge

Every knowledge has a perention date. The Earth has long been considered as flat before Magellan brought the practical evidence of its roundness. By the same token, everything you learn about computing, you will have to unlearn it one day. (Don’t panic, your memory will do the trick without you even being aware of it.)

If you have more than a few years of experience as a software developer, you already experienced that. This is fairly obvious concerning frameworks. Frameworks are often getting a lot of attention, and if we compare them to nature, they are ephemeral, like beautiful flowers. They will wither and disappear.

Therefore, if most of your time is spent learning frameworks, you are cultivating a field of flowers but you are not really exploring the world around you. Year after year, your landscape will look unchanged. Flowers will be different but we will still be at the same place.

You can spend your whole career growing plants or you can leave your meadow for hiking.

The Ascension to Expertise

Nobody is expert after graduating. You have to focus your attention on a particular subject, for a hill to turn into a mountain. “The man who moves a mountain begins by carrying away small stones,” said Confucius. Even the Himalayan Mountains are still growing after 50 million years of existence!

Expertise requires time over talent. How much? It mainly depends on the discipline. For example, as the number of developers increases, the time to reach true expertise increases as a result. However, new subjects appear like blockchains in recent years, for which you may pretend expertise after a relatively short time, in the same way that a volcanic mountain forms in a relatively “short time” compared to mountains formed by plate collisions. But this situation will not last for too long, and you will have to work hard to stay on top. Expertise is hard without perseverance.

In addition, mountains rarely stand in isolation. Most of them stand in a range, like Mount Everest, which is located in the range of the Himalayas. The higher the mountain, the more likely it is surrounded by vast mountain ranges. Similarly, expertise rarely stands in isolation. You need to justify a solid foundation on many related domains—you cannot climb Mount Everest if you have never climbed smaller mountains first. For example, you cannot rank at the top of programming contests without a solid background on algorithms, data structures, mathematics, and statistics.

Expertise is a long walk. It has no end. “You’ll never know everything about anything, especially something you love” said the American chef Julia Child. You can always climb higher and get better at what you do. This is why there are clouds hiding the mountain summits in the illustration above. It’s impossible to evaluate how high the mountain is—you can only determine your altitude and observe the fruit of your effort by standing where you are.

The Desert of Ignorance

Even if you spent your entire life learning, there will always be subjects you’ve never heard from. In fact, ignorance is an integral part of the learning process. The less you know, the more you can learn. And the more you learn, the more your ignorance becomes evident.

The oceans cover 71 percent of the Earth’s surface. That’s a lot, but if we look at the knowledge map of anyone of us, ignorance would for sure occupy an even larger space.

Lost in the middle of these deserts of ignorance are oases, fertile spots where water is found and palms grow. Indeed, there are many subjects (if not the majority), for which we have barely scratched the surface. For example, we have read a tutorial on a new framework but that doesn’t mean we are ready to use it on production. Remember that the most beautiful oasis is always surrounded by desert. Don’t pretend to be an expert when you are standing in the middle of the desert.

The desert is an hostile environment where few species are able to survive. Planting a tree in the desert is not a good idea. Vegetation blossoms when the soil is fertile, and the rain is falling. Don’t learn a web framework without learning JavaScript first. I’m sure that you will never adventure in the desert unprepared, so don’t try to learn without the prerequisites.

We can apply the landscape analogy to the developer types identified in the previous post.

- The Dash-Shaped Landscape looks like a flat landscape, dominated by the desert, with oasis representing prior experiences and a few hills representing the current interests of the developer.

- The I-Shaped Landscape looks like a mountainous landscape, surrounded by the immensity of the desert.

- The T-Shaped Landscape looks like a rich and varied landscape, with a few mountains surrounded by green hills.

Before closing this section, we must highlight that depending on your areas of interest, an arid desert for one person will be a lush meadow, or a gorgeous mountain for another person. Among coworkers, you may expect a lot of overlap between their knowledge landscapes, but no two landscapes will look perfectly the same. We’re all coming from different backgrounds, we’re all reading different materials, and we are all addressing different challenges every day. This explains why no two persons are interchangeable at work.

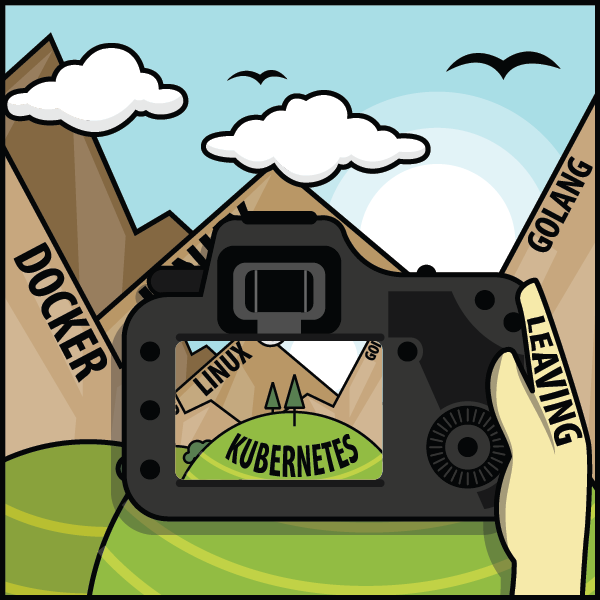

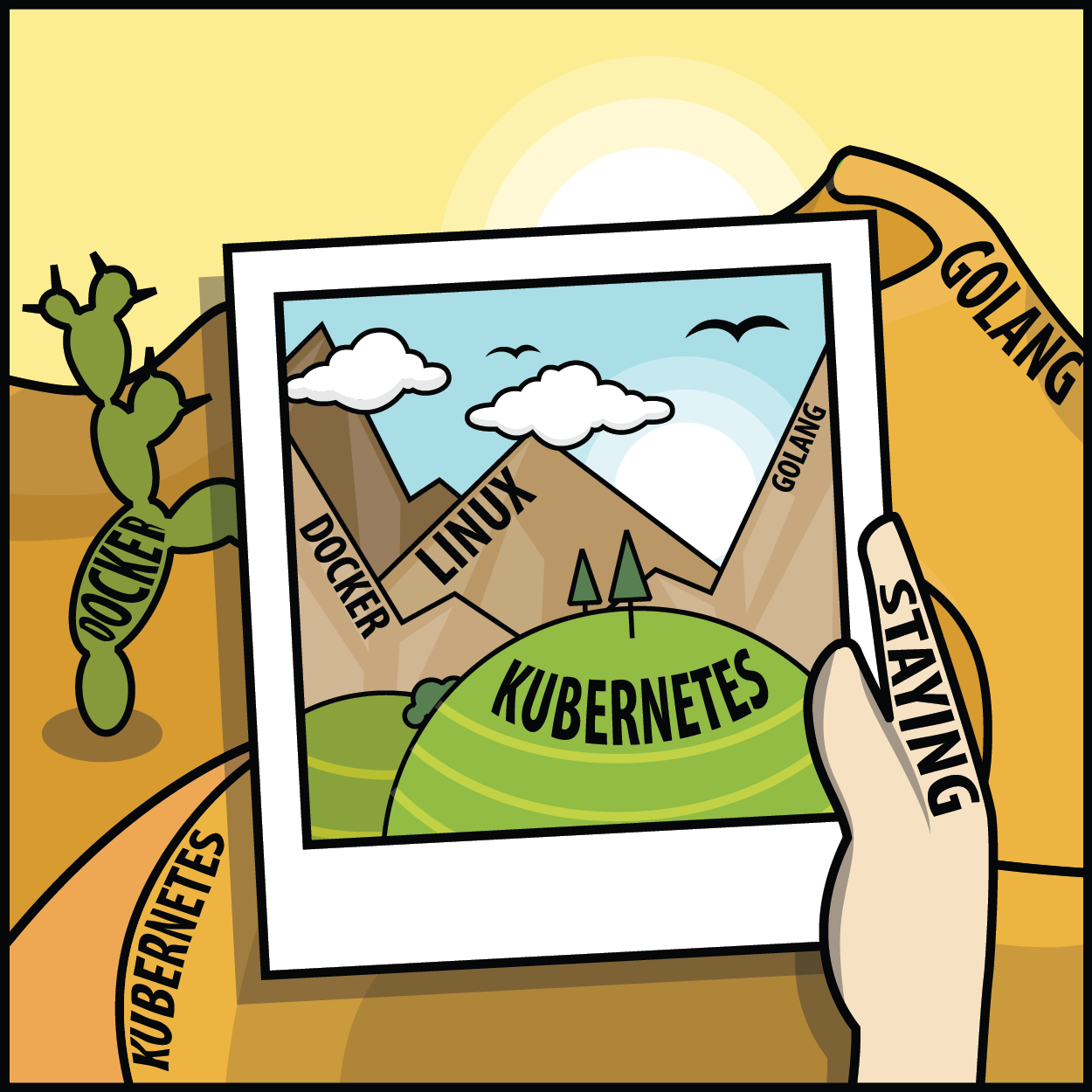

When someone is leaving a company, she is often responsible for transferring her knowledge during the offboarding process. But you can’t really transfer knowledge between employees. That would mean moving entire squares from one landscape to a different one. We don’t know how to do that.

What happens generally is that the leaving employee does her best to capture what she judges important, taking pictures with her camera while hiking in her knowledge landscape. But even the best travel photography book will never capture the full complexity of any landscape. The camera puts the focus on a particular subject. There are a lot of blurred details. The angle will be too wide, or too narrow on some pictures. In short, you will lose a ton of precious information.

As a manager, you should make sure that coworkers share a lot of common grounds with the leaving employee, so that the distance they have to travel in their own knowledge landscape will be relatively short, preventing them from running a marathon until exhaustion.

Learning As a Gardener

Our knowledge landscape is always in motion like the earth is constantly facing changes such as global warming. Even if we stop learning and do absolutely nothing, our landscape will still evolve, as we have no way to prevent memory decay.

The forgetting curve depicts how quickly we forget information over time. If we don’t use a piece of information, we lose it. It’s as simple as that. Therefore, your actions determine the future of your landscape. It can evolve in a gorgeous landscape of contemplation, or an arid landscape of desolation.

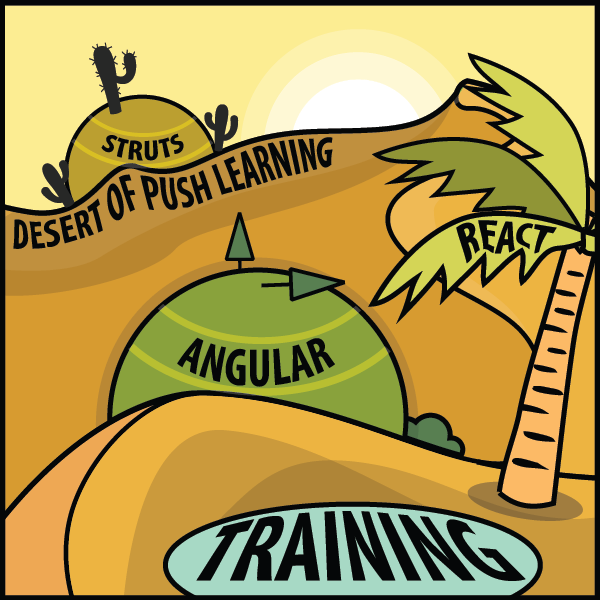

The dryness of push learning

When you stop learning, deserts are progressing and gaining surface, like they do on the earth. Knowledge becomes superficial. What was a beautiful tree not long ago, is now a cactus. You can still answer the most basic questions, but others will have no problem finding someone else more knowledgeable without thorns on him.

Sometimes, an oasis appears in the desert. Your company enrolls you on a training course, and a previously unexplored path turns into a now familiar territory. But cramming too much information in a few days is not the best strategy to build a solid understanding on any subject. You need, instead, to continue learning, to put it into practice, to convert this oasis into a hill where flowers can blossom. On the contrary, if you stop using a particular technology, for example after a career move, a meadow will turn into an oasis, before being just sand.

Self-education is, I firmly believe, the only kind of education there is.

— Isaac Asimov

With group learning, everyone is starting from a well-defined place in his own knowledge landscape. For the instructor, it’s hard, if not impossible, to provide clear directions to the group. Some will have to cross deserts (if they don’t have the prerequisites), while some will have to go down (if they are already familiar with the topic). If the instructor fails to understand where people are standing in their landscapes, some will inevitably get lost, and some will inevitably get bored.

Group learning works best when there is a lot of overlap between the different landscapes, what is true during our first years in school, but what is not true in the professional world.

On one side, the apparition of the desert is a blessing. Technologies appear and disappear constantly. Not long ago, we were exposing SOAP services, we were generating views from backend servers, we were creating desktop applications instead of web applications. What’s the point in remembering all these technologies if we will not use them again? Our brain knows that. We can count on its natural ability to clean the faucet everyday (the more you’ve used a technology in the past, the more time is required for the faucet to do its job).

On the other side, too much desert is dangerous. In an ever-changing world, the vast immensity of a desert may seem like a relaxing place, but in the workplace, finding a job when you are lost in the middle of the desert is never a good idea.

The wetness of pull learning

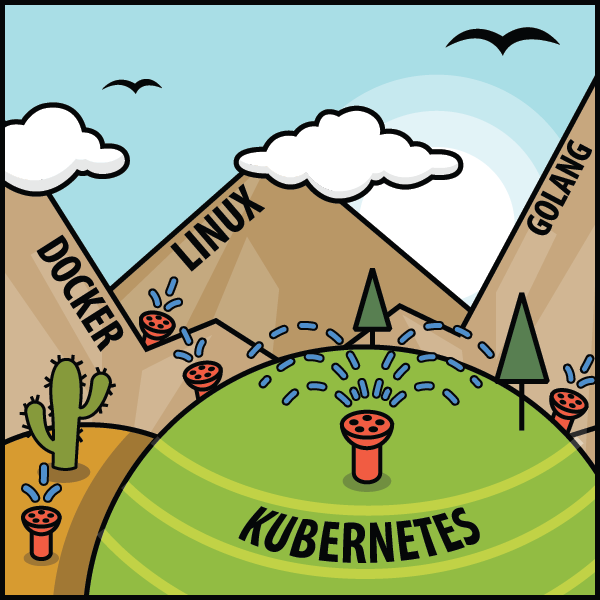

To slow the progression of the deserts, the only option is to review and practice regularly to keep your knowledge up-to-date, reversing the effects of the forgetting curve. Learning is not an activity you can do occasionally. Learning is a way of life.

When you are reading a book, attending a meeting, creating a pull request on an OSS project, following publications on Twitter, each one of these actions is like adding a sprinkler somewhere on your map. With enough water, a desert turns into an oasis, an oasis turns into a new meadow, a hill turns into a mountain, and the cloud at the top of the mountain finally fades away to reveal another cloud closer to the summit. You are expanding your knowledge!

You must always remember you are alone in your knowledge landscape. Therefore, you are the only one responsible to preserve it. Best companies understand learning is crucial, and thus offer a ton of opportunities for employees to keep learning. That’s great. Even better, you must learn not to expect anything from others, from your companies, from your coworkers. Lifelong learning is the only solution to nurture your landscape over time. Remember that there are no gardening mistakes, only experiments.2 “Simply” learning something new every day is enough to provide the water your landscape needs.

Pictures of Landscape

In this section, we will apply what we learnt through practical examples, reflecting situations we encountered at work.

The Prerequisites

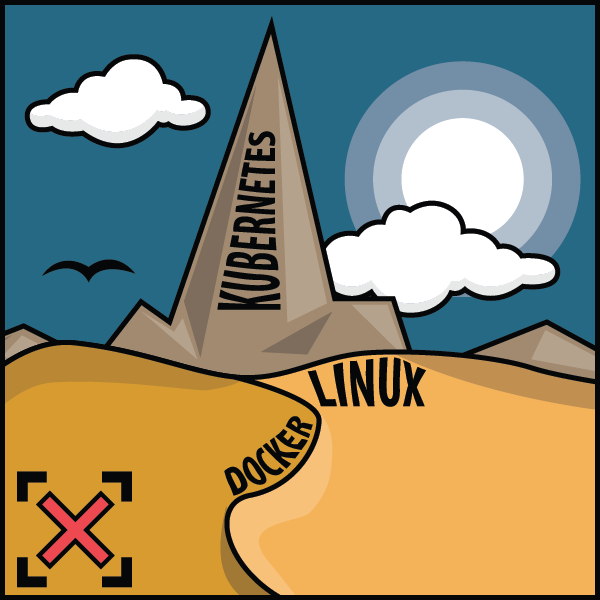

Prerequisites are important to smooth the learning experience. If I talk to you about dynamic programming, but you’ve never written an algorithm, it’s only gibberish. This applies to everything. If you read an advanced Python book but you’ve never written a single line of Python before, you will find the book awful, unfairly. Similarly, if you attend a training session about a new framework without experience using the underlying programming language, you will have a hard time. The situation looks like the following illustration.

Climbing the mountain in the first picture is not impossible, but it will take a lot more time, as you will face many barriers to overcome. The mountain in the second picture is the same mountain but when prerequisites are satisfied, the challenge seems a lot more approachable.

Therefore, when something seems too hard, acknowledge it, find something simpler to learn first, and revisit the material later, better equipped with stronger foundations. Take the time to grow your landscape.

The Applicant

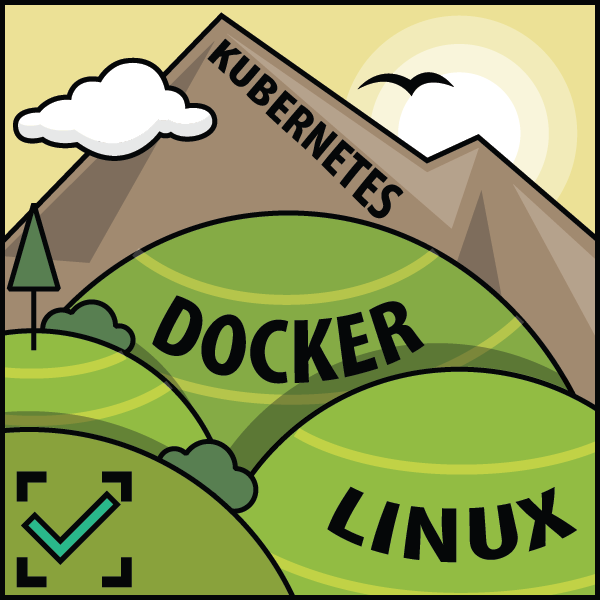

Almost all job openings list the minimal or expected qualifications. Depending on the companies, we may classify those job offers in two broad categories.

The first category usually concerns small to medium companies looking for an applicant to fill a vacant position (in practice, this concerns most of the job openings on career sites). The applicant needs to be a good fit for a particular project, and attests prior experiences on the same or similar technologies the team is using. The onboarding process will be short and the newly-hired staff needs to be effective as soon as possible.

The second category is popular in large companies such as Google and Amazon. These companies are constantly hiring new recruits, which will be dispatched in one of their numerous teams. As the company doesn’t know in advance the final assignment, they are looking for talents fitting the company culture. Candidates will commonly be asked to solve a system design problem and an algorithm puzzle, in addition to classic HR questions.

These two approaches are looking for candidates with very different skill sets, and thus very different knowledge landscapes as outlined by these illustrations. Which approach is preferable?

Clearly, the second one is a good strategy to limit false positives. Indeed, you have to work harder to be able to succeed in the interview process. You need to practice a lot on coding challenge websites during a few months to be able to solve moderate problems. It demonstrates perseverance, a rare, valuable quality that is known to be key to success.

On the contrary, a previous job experience using the same technologies is enough to match a job position in the first category. Of course, you will have to make a good impression, and justify your skills, but no prior preparation is really required. The company learns you are knowledgeable about a small subset of subjects, but the company learns nothing about the qualities you may or not have and they will need to succeed tomorrow.

Mixing the two approaches is not the solution. Some companies adopt the interview process of Internet giants but fail short as they don’t have the same acceptance criteria. Asking easy algorithm questions do not bring the same insights as difficult ones, as the candidate does not need to practice as much to succeed. Companies get the disadvantages of both approaches without the benefits of either.

The Illusion of Competence

Many students experience illusions of competence when they are studying. When you have the answer in the textbook in front of you, you may think it is also in your brain … until you pass the exam and flunk. The solution to this problem is self-testing. Don’t read a book passively. Try to recall the main facts every few pages. Don’t read the solution of a math problem. Try to solve it first. In short, try to engage with the material.

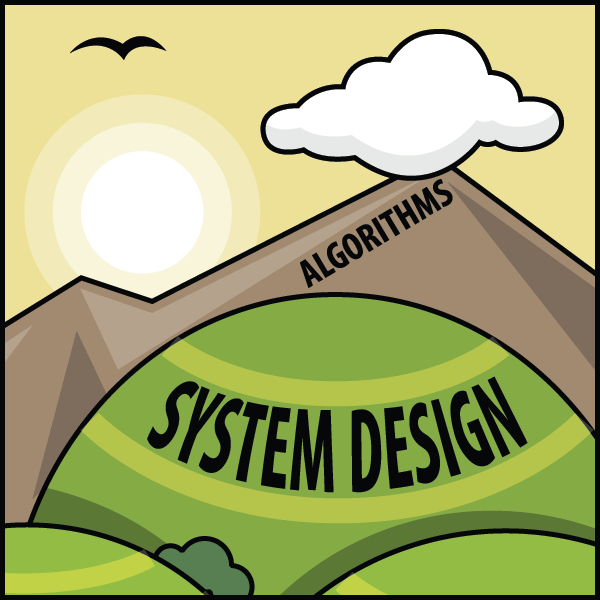

This phenomenon is also frequent in the workplace. We have all run into coworkers who think they know everything but their work says otherwise. They attend a meeting about a new framework and now pretend to be experts. This situation is depicted in the following illustration.

This trait is particularly accentuated among developers. When someone asks us “Do you know about technology Y?”, we often say “yes” even if we have just visited the homepage of the website. Saying “I don’t know” is not so easy. Feeling incompetent is feeling threatened. But it’s the first step towards learning.

The Impostor Syndrome

Many people refuse to acknowledge their accomplishments and competencies. They attribute their success to luck or fraud. They happen to do well until now, but are pretty sure on the next challenge, people will finally figure out how incompetent they really are. Those persons experience a phenomenon known as the “impostor syndrome.”

You are good at your job, you know your subject, and yet you feel that you are not as competent as your teammates. You feel alone in the desert, when in reality, you are helping your team to climb a new mountain.

Overcoming impostor syndrome imposes to separate the feeling from the facts. Open your eyes and observe where you are right now, and the long journey you did to stand here.

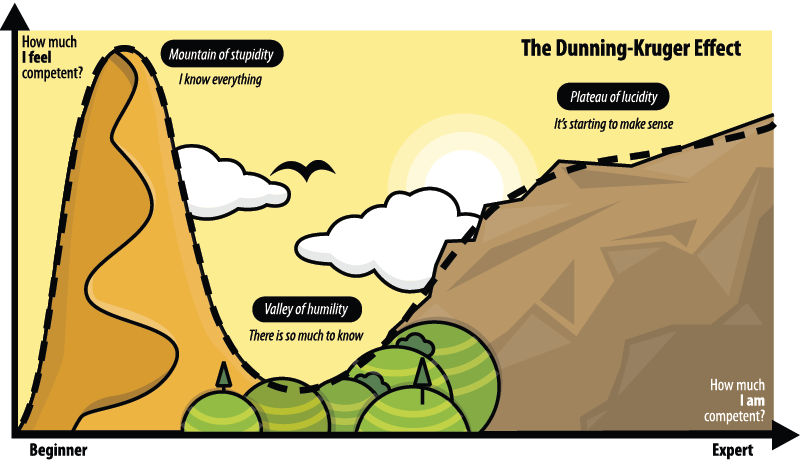

The Dunning-Kruger Effect

At low levels of performance, people tend to presume they are much more competent than they are. Inversely, highly-qualified people tend to undervalue their level of expertise, and often presume tasks that are easy for them should be easy for others too. The Dunning-Kruger Effect can be summarize as “stupid people have no idea how stupid they are.” It’s the classic example of the illusion of competence.

When learning something new—a new framework, a new language—you are progressing so fast during the first hours. You may think that you have climbed a mountain, when in reality you have just reached the top of a dune. If you stay at that position for too long, you will experience the illusion of competence. But if you continue your journey, you will discover that things are not so obvious, and there is so much more to know. Now, you can start experiencing impostor syndrome. You feel incompetent even if you have gone farther than most people on the subject. Slowly, you put parts of the puzzle together. You are climbing towards expertise. It’s a long ascent with intermediary plateau to observe your progression and refill your battery, before going higher and higher.

The Dunning-Kruger effect underlines the biggest challenge concerning learning: how to judge our own progression? How to find balance between the impostor syndrome and the illusion of competence? There is clearly no easy answer, but between feeling competent or incompetent, you must learn to prefer the second option.

The Ideal Landscape?

The earth is so wonderful that trying to reach agreement on the most beautiful place is useless. Learning is no different and there is not an ideal landscape. Being at the top of a mountain when your current employer expects you to be proficient with the latest, popular frameworks is not very useful. Knowledge is only relevant when applied in practice. Therefore, you need to create a landscape that is the most versatile for your current job, or find the job that is the most relevant for your landscape. In practice, you can stand between these two extremes, living in a landscape partially adapted to your work, and partially adapted for new job opportunities.

What is really important, however, is to be conscious of where you are and where you go. Do you want to spend your whole career in the meadow learning frameworks? Flowers are beautiful, but fragile. A gust can ravage your landscape and transform your greeny meadow into an arid desert where your employment value will be severely damaged.

The ideal landscape is the one that is becoming increasingly rich and complex over time. There is no end in learning and therefore, there is no final destination to reach. Learning is a lifelong process. When you are steady, you are not learning. Learning means moving from where you are now to a new place, and observing with attention all around you. There are so many things to learn that are just one step from you.

It’s time to move on, and read the last article of this series where we will talk about expertise.

Footnotes

-

https://www.onlinecoursereport.com/the-50-most-popular-moocs-of-all-time/ ↩

-

This quotation is attributed to Janet Kilburn Phillips. https://www.oldtownbloomers.com/post/there-are-no-gardening-mistakes-only-experiments ↩